Missing the Language Long Lost: A Trail of Mysterious Books

What Orwell teaches us about writing and how internet language rots our brains

To expand and rewild your own writing and reconnect with the inner writer, join my Headwaters 6-week online writing course, designed to deepen your authentic writing practice and unblock your creative life force energy.

We start October 30th 2025.

The writer either has a meaning and cannot express it, or he inadvertently says something else, or he is almost indifferent as to whether his words mean anything or not. This mixture of vagueness and sheer incompetence is the most marked characteristic of modern English prose, and especially of any kind of political writing. As soon as certain topics are raised, the concrete melts into the abstract and no one seems able to think of turns of speech that are not hackneyed: prose consists less and less of words chosen for the sake of their meaning, and more and more of phrases tacked together like the sections of a prefabricated henhouse.

— George Orwell, Politics and the English Language (1946)

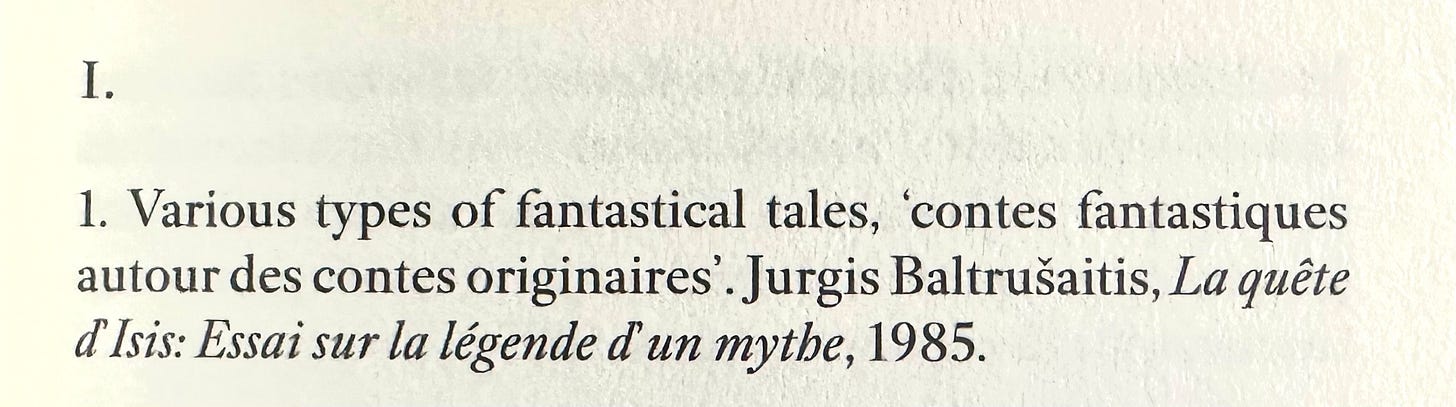

One Saturday afternoon my partner pointed at a book “The Ways of Paradise”, published by Fitzcarraldo Editions. ‘I think you might like this’, he said in a lowered tone. We were in Berlin’s largest bookstore. The book was a strange arrangement of research and 122 loose notes, a manuscript with no clear pattern, gathered by a Swedish researcher. I opened the book and the very first note said this:

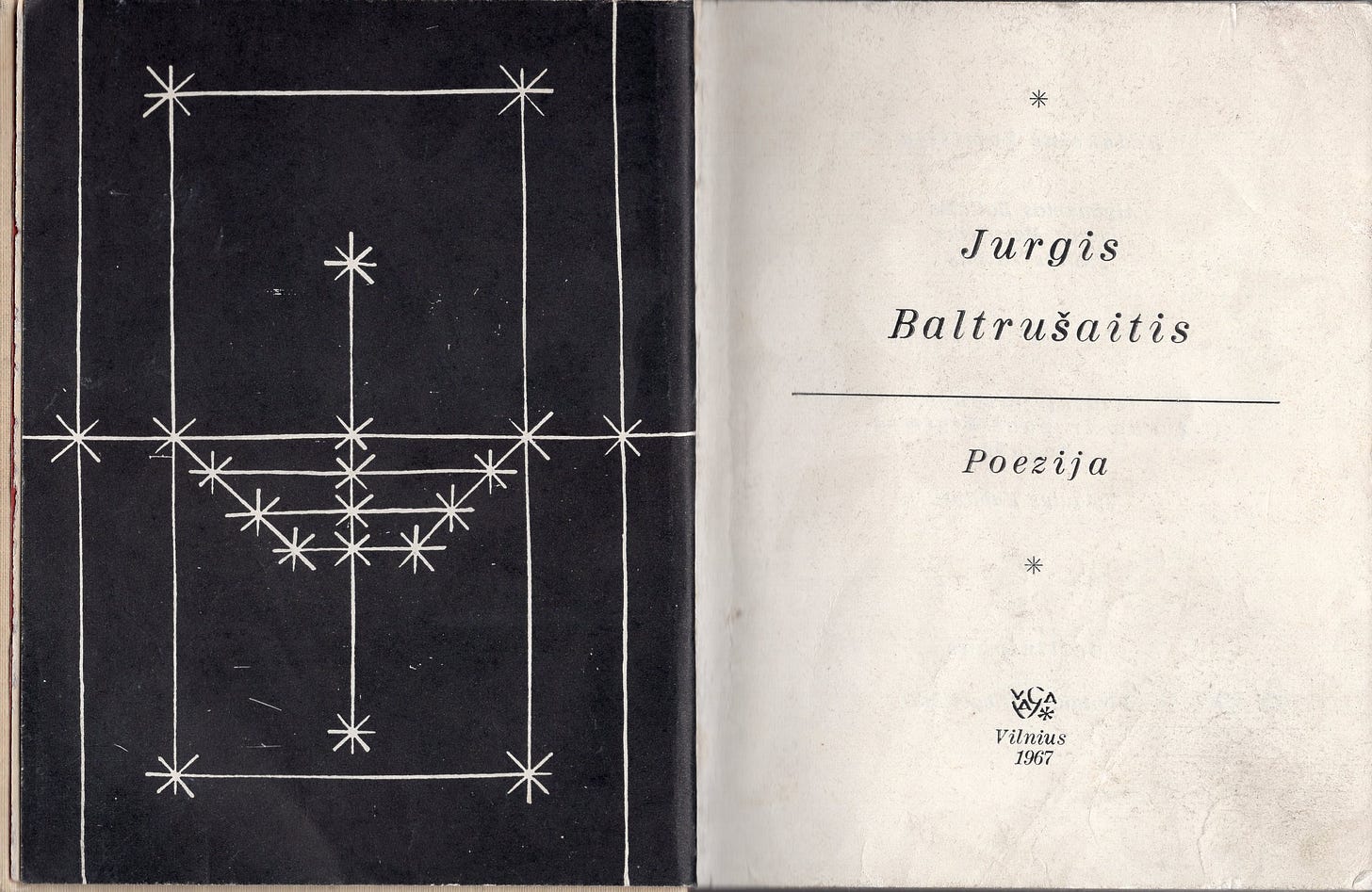

Wait a minute, I thought to myself. First of all, I am buying this book. I love books that are weird, unexplained. Second of all, Jurgis Baltrušaitis was a Lithuanian poet, whose poetry book I happen to have at home. The mystery was piqued.

We came back home, I found a copy of the poetry book by Baltrušaitis on our shelf. Small, canvassed cover with a minimalist graphic design. I started reading the preface in Lithuanian, written around 1964. At the time Lithuania was still in the depths of the occupation by the SSSR. The government of the time was combing all the books for unnecessary patriotism, and this one somehow slipped through the cracks.

The way the introduction was written felt so alive, unobstructed, energetically rich. It was following the life of the poet, his self-created exile, his life in Moscow, Norway, and Paris, then war, and finally a return to his own roots. There was so much nuance and detail, and tacit information in the language. Reading Lithuanian in the pre-internet era, speaking about the poetic symbolist movement, metaphysics, and literary and political shifts of the time, created a very strange recipe for psychic food that I didn’t expect to receive. (Mind you, this was not even the poetry itself, but the introduction.)

It’s been a while since I read something like this. I wish I could translate it, but in actually, I don’t wish for that at all. The only beauty that we have left in this world is untranslatable, uncyphered. I am happy to be one of 8000 people who have this book, not more. I find strange reassurance, beautiful synchronicity through time when I find books referencing each other. My neurodivergent brain rejoices.

As I read the introduction, I felt a tectonic plate shift somewhere within me. Maybe I can call it a spiritual experience, a new energy downpour. It’s as if I was awoken from the dullness of language I am so used to these days — the internet language.

I felt frustration, even anger. I’ve grown to read only English contemporary texts, palatable to a Westernized nervous system and worldview. Now, I am not saying internet writing is not interesting, or lacking depth, or insight. There are so many beautiful contemporary human experiences. What I am saying is that it’s sickening how fast we get used to a certain kind of literary diet.

Reading something that is solely born on the internet feels strangely isolated by a certain kind of self-referential banality. There is no feeling. I have become accustomed to not feeling much of the English language in general. Perhaps, because I was not born into it. I will never be. I am a silent observer, a borrower. There is a gap between me and this language, and it will never be closed.

(It’s not about those beautiful quirky digital gardens that we can find and confide in. Some writers still manage to arrange language in a way that still makes me feel certain tinge of aliveness, but it’s rare. If I find them, I want to hold onto them. Dearly.)

The language that we write with on the internet today appeals to the reptilian part of the brain, not the higher self, not the body, not the soul, not the mind that desires strange novelty. The text is chewed up for a certain relatability, lacking vitality or a reflection of life that feels deeply personal, human. The way we address each other, the way we address the reader are diluted in attention-seeking writing practices. It serves only the writer and their ego. Some writers (and publications) resist against this large current, but the majority reinforce the inertia. Seeing clickbait, even subconsciously, chips away at our capacity to think outside of this language frame, let alone write outside of it.

It would be hard to explain why this is all happening. But I might attempt, so I ask for your patience.

English is not my first language. I will never be able to write in full fluency as a mother tongue English writer. At some point, my expression is capped, because at the fundamental level of my neural architecture is the language that I spoke from birth. English cannot compete with it. (Niels, my fiance still makes fun of me for strange sentence structures and insufferable amount of commas.)

It’s as if Lithuanian has flooded the bottom floor of my subconscious, and whatever other language you may try to put down on the floor, the water will float it up. It sits deeper between the tissues, on a somewhat cellular, even atomic layer of my being. Poems that I read at 15, on a bench with old, peeling paint, by a shallow winding river, are still within me.

I can only explain that sudden awakening moment of lost my “lost” language (and my new disgust towards the use of language today) by looking back at of all that soaked up literature in the early years. Not that I read a lot as a teenager, but I managed to find work that really moved me. It’s as if a writer was a musician, who struck a violin, and the vibrations reached another violin’s body—reverberating it through the law of resonance. So did those texts in the early days affect me, resonate in me. It’s not even the words themselves, but the states of being that they were able to transfer, was the most important thing. Still is.

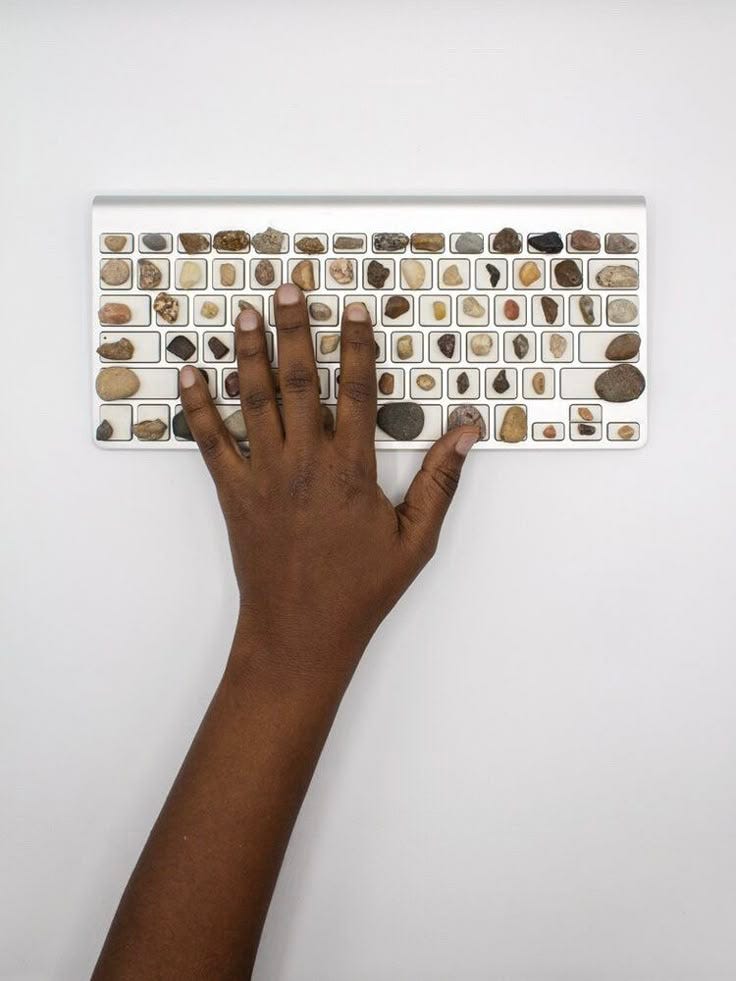

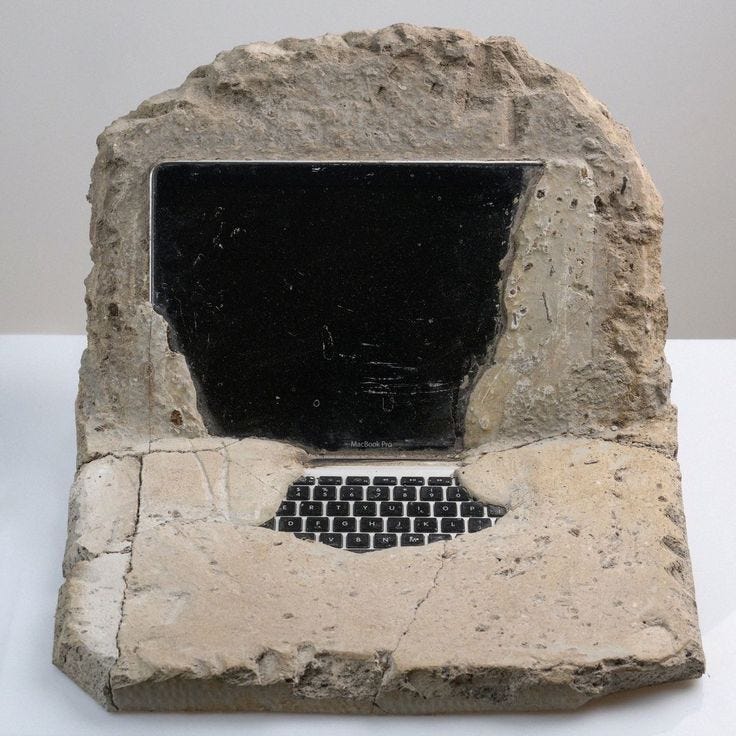

The language of the internet today fully taps into its scarcity, its hooks, its immediacy is derived from well-funded psychology labs and chewed up by the pop culture of self-help writers. It is engineered for a short attention span, for a person who has no time (by the design of the system), and will benefit from skimming the information. It has no lasting value. Unfortunately, we see how well it is performing, we absorb it, and the worst — we emulate it.

I don’t want to see another list. I don’t want a general introduction or a summary. I want a human (or a more-than-human) story that forces me to feel newness and obliterates any stagnation and inertia in my mind. I want to go on a journey, not knowing where it will lead me.

The Problem of Relatability

In 1946 Orwell argued that the English language, especially prose and political language became devices of obscurity— ”[it] is designed to make lies sound truthful and murder respectable, and to give an appearance of solidity to pure wind.”

I must admit, I do enjoy the brutality of Orwell’s approach to writing. I think it’s an essential read for everyone who wants to write better:

By this morning's post I have received a pamphlet dealing with conditions in Germany. The author tells me that he "felt impelled" to write it.

I open it at random, and here is almost the first sentence I see: "[The Allies] have an opportunity not only of achieving a radical transformation of Germany's social and political structure in such a way as to avoid a nationalistic reaction in Germany itself, but at the same time of laying the foundations of a co-operative and unified Europe." You see, he "feels impelled" to write — feels, presumably, that he has something new to say — and yet his words, like cavalry horses answering the bugle, group themselves automatically into the familiar dreary pattern.

This invasion of one's mind by ready-made phrases (lay the foundations, achieve a radical transformation) can only be prevented if one is constantly on guard against them, and every such phrase anaesthetizes a portion of one's brain.

The vague language of war politics is not gone, certainly not from the mainstream media.

However, the gift of free rein, free expression has swayed to another direction. Now everything is easy to understand, personal, and relatable. We’re all being exposed to this language all the time, we’ve all written in this way. But I don’t know if it benefits us. Every viral essay that I read says something that I might intrinsically know, but nothing changes, nothing is renewed in me, no new ideas spark. I feel silly for getting hooked on the algorithm’s bait.

On the one hand, Orwell got what he asked for: a simple, relatable, short language of the commons. But we swayed to another direction that feels just as bland and malnourishing: relatability.

Relatability is the chief psychological lubricant that glides you thoughtlessly down the curated, endless scroll of your feed.

—Why Do We Obsess Over What’s ‘Relatable’?, Jeremy D. Larson

Everyone has become relatable. You enter into a para-social relationship with everyone. This type of relationship is what the internet is built upon. Because a human being is an animal, it seeks relationality, connection, belonging, and affirmation that it’s not alone. But this desire to mimetically belong is weaponized by commerce, by media, and by mainstream stories. Those whom we repeatedly see on our screens, those whom we listen to and read, we internalize and create one-sided bonds with. We create a one-sided trust.

Relatability today is a short hot flash of dopamine. It’s a meme. It infinitely scales until it unites everyone who can relate. It doesn’t ask the creator/writer to do the work. The work I am talking about is the work of mining your psyche for a human story, not relatable in pure the aesthetic decree, not even a plot — but a pattern of feelings, thoughts, and relationship dynamics that externalize the dramatic nature of life. These run deeper than the appearance of things.

There is a big difference between viral relatability and a writer being able to excavate a piece of work that directly addresses parts of you that you didn’t even have courage to acknowledge.

I still think of Left Hand of Darkness by Ursula K. LeGuin. Can I relate to the main protagonist being a tall black man, an envoy on a permanently frozen planet, involved in political manipulation, surrounded by a non-binary race of humans?

No. But what I could relate to is a tacit friendship that builds over hardship. I could relate to unspoken aspects of attraction between two strangers. The part of me that felt seen, was the part that valued friendship that belongs in a realm beyond words. Awkwardness, ambiguity, shyness, self-preservation, yet somewhat devotion and loyalty. This is the intricacy that is a very rare experience in reading.

I want to hold onto stories that have lasting value. I want to internalize them. I want to open myself further to allow them to affect me. But to do that, I cannot be open to stories and content that grab my attention and run in the opposite direction.

I long for language that can push and rearrange my imagination, that shows how wide my mind is. Almost a dream language, one that spews images and allows my brain to create some kind of sequential story from those images.

I also want language that I can still understand, that feels familiar, but not relatable to the shallow parts of my psyche.

Can you relate to this?

The only novel thing is timelessness.

Memes will disappear into oblivion. So will the immediate content, so will candid opinions will pop-culture pieces that seem to circle the 30 year period (from the 90s onwards). In the very near future, we will see that the insatiable hunger for relatability will be satiated, overflowing into the gutter. What will come, is the desire for unrelatable, unknown, alien, strange, distant, mystical, uncomfortable, ambiguous. I can hear that desire within me loud and clear.

A well-prepared, emptied mind will receive art and stories that are getting ready to materialize themselves on Earth. Inspiration or an idea, in a filled mind will not be noticed, will not be recognized as valid or valuable, and most sadly — will be mistaken for content that has already filled the mind.

Just as the immune system in the human body is able to detect a pathogen within and destroy it, we need to grow the immune system in our minds. We welcome foreign pathogens into our mental, emotional, energetic space all the time, but compared to body’s immune system, the elimination process is much harder. That’s why it’s so important to shield ourselves from entertainment that pollutes.

Our eyes need protection, our ears need protection, our minds need protection from the language of the internet.

Below I share my protocol for depth and vigour when writing and renewing the inner language sensorium.

“If people cannot write well, they cannot think well, and if they cannot think well, others will do their thinking for them.”

― George Orwell

Protocol of Depth and Vigour

If you made it this far, here is a reward. A small protocol for re-gaining the relationship with language that invigorates you, which I too, intend to follow in the coming weeks. I hope to report on the failure or the success of it. (Please comment if you have any other tips or texts that have reinvigorated you.)

Time to renew our writing sensorium.

I invite you to seek reading experiences that shake up your understanding of language and communication. This will change the way you think and write. Especially in your mother tongue language. Especially if you’re used to consuming everything in English.

What happened to me with that little poetry book was something that I don’t think I can re-create in the English language (yet).

Go on a content diet. Don’t read that viral essay (ugh it’s so hard). Don’t click on the clickbait video. Allow your mind to take a break from conversational written English.

Practice writing in an unfamiliar way. In the essay Politics and the English Language, George Orwell describes the writing process that can jolt a reader out of a dull disengaged state into a state of aliveness and alertness. I love it and I want to share it with you:

What is above all needed is to let the meaning choose the word, and not the other way around. In prose, the worst thing one can do with words is surrender to them. When yo think of a concrete object, you think wordlessly, and then, if you want to describe the thing you have been visualizing you probably hunt about until you find the exact words that seem to fit it.

When you think of something abstract you are more inclined to use words from the start, and unless you make a conscious effort to prevent it, the existing dialect will come rushing in and do the job for you, at the expense of blurring or even changing your meaning. Probably it is better to put off using words as long as possible and get one's meaning as clear as one can through pictures and sensations.

Afterward one can choose — not simply accept — the phrases that will best cover the meaning, and then switch round and decide what impressions one's words are likely to make on another person. This last effort of the mind cuts out all stale or mixed images, all prefabricated phrases, needless repetitions, and humbug and vagueness generally.

Much love,

Rūta

I feel like this entire piece could be an excellent invitation for an in person debate. You write with much passion and conviction Ruta - your words are thought provoking and I deeply appreciate that you’re not leaning away from making a reader ‘uncomfortable’.

Your take on relatability is interesting and I think it applies to all spectrum of our life. Just yesterday I had a conversation with a friend, who’s a director of the Politics and Gender department, about the fact that we both, subconsciously or not, surround ourselves with people that echo our way of being in the world. After many cups of blueberry leaf tea, we concluded that bringing about change - whatever that means to you - perhaps can be even more meaningful if we continue to have these types of interactions outside of our bubble. I highly doubt this is going to be comfortable - but without a doubt - it’s going to be meaningful. Whether relevant or not this came to my mind while reading the paragraph.

Finally, the ‘irony’ that your piece ends with a list - it’s not lost on me 😉

Thank you 🙏🏻

This piece is brilliant Ruta, thank you so much, it deeply moved me.