Refusal to Heal — Mycelium Sculpture Project

Mycelium, exhibiting my art, ending extractive relations, and healing.

Short announcement_1: For those in Berlin (Germany), I will be having my first co-exhibition in an ongoing project MY-CO PLACE at BHROX, June 26—July 2.

Exhibition opening: June 26, 7PM. In the opening, I will be exhibiting Refusal to Heal project prototypes and give a short presentation. Hope to see you there!

Healing in a Profoundly Sick Society

Sometimes the underlying essence of healing on society’s terms means adapting to profoundly degenerative structures that allow further extractive relationality. Here, maladaptation is framed as healing that allows us to come back into colonial architectures that expect us to be agents of productivity, further fuelling the paradigms of exponential growth. Sometimes healing means that we will be thrust back into linear, non-cyclical movement forwards that asks us to grow exponentially, to grow without awareness, to produce a garden for high-yield consumption at the cost of depletion.

And so, the question arises: what is true healing?

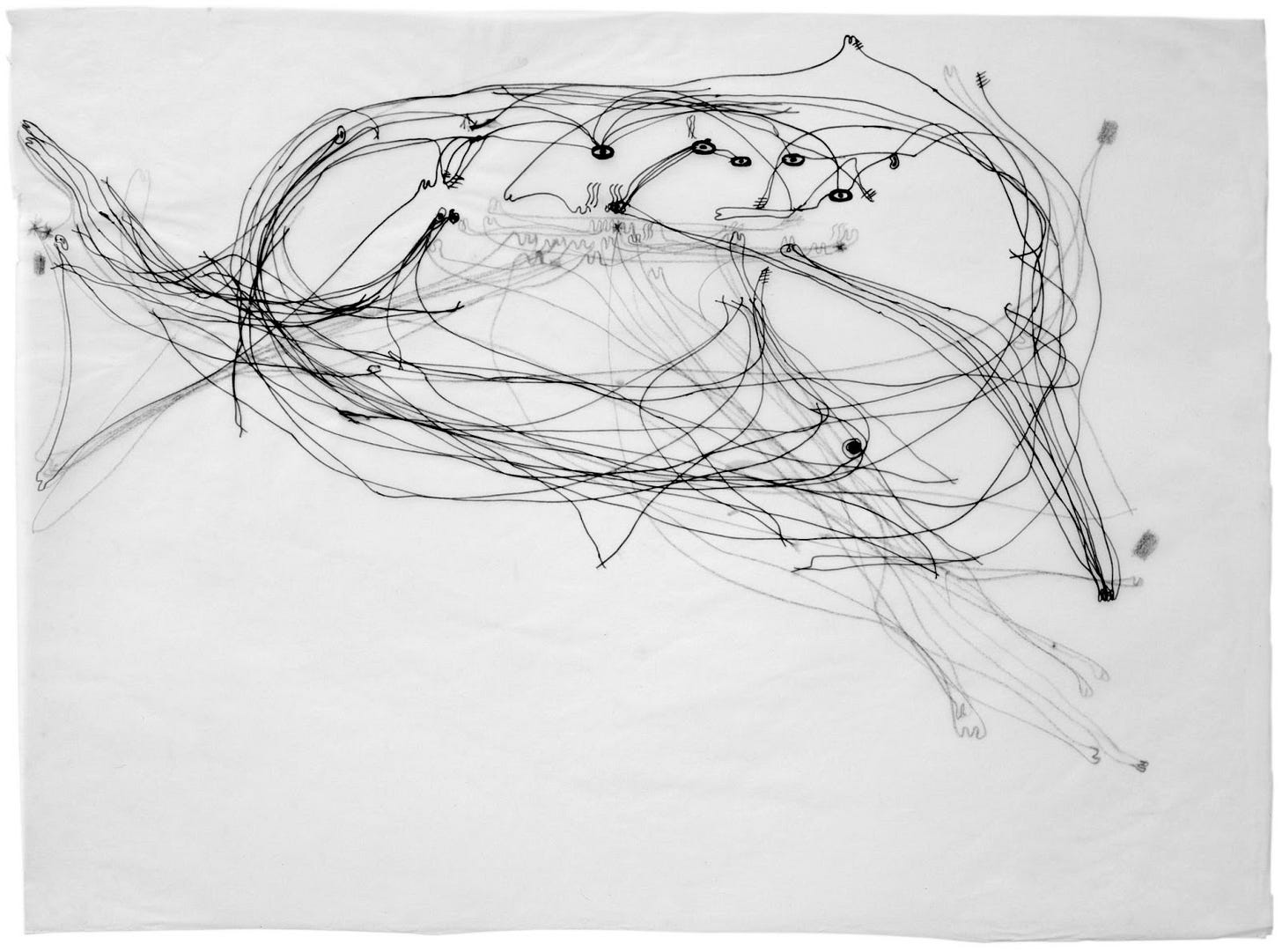

In my latest and ongoing science-art project called Refusal To Heal, I want to explore the juxtaposition of healing. The artwork is a fungal mycelium sculpture, shaped into a humanoid body, and contained in a rectangular glass container. Here, mycelium is a co-designer, co-artist, and co-remediator. It lends the quality of an alien, unknown, distant, yet deeply familiar. Allowing us to look at and reconnect with the alienated parts of the collective psyche and the collective body.

The project aims to provoke a public discussion of what it means to adapt to systems detrimental to our well-being, and what happens to our body-mind when we overlook signs of internal resistance. Leading traumatology researchers suggest that trauma happens when we lose connection to our authentic selves, replaced by adaptation to surrounding circumstances. In a viral article “I’m a psychologist – and I believe we’ve been told devastating lies about mental health” in The Guardian, author and clinical psychologist Dr. Sanah Ahsan writes: “But change won’t happen without us: our distress might even be a sign of health – a telling indicator of where we can collectively resist the structures that are hurting so many of us. <…> The most effective therapy would be transforming the oppressive aspects of society causing our pain. We all need to take whatever support is available to help us survive another day. Life is hard. But if we could transform the soil, access sunlight, nurture our interconnected roots and have room for our leaves to unfurl, wouldn’t life be a little more livable?”

Refusal to Heal aims to reveal the parts of the human psyche that want nothing to do with healing back into society or a life that will not change. These parts of us manifest as inexplicable ailments, chronic conditions, somatic disability, neurodivergence, ADHD, high sensitivity (HSP)—everything that is perceived as unproductive—causing the slowing down of a growth-obsessed economy. Resigned to the shadow, these parts of us seek relationality, unconditional being, truth, and a conversation no one dares to have. These parts are described as resistance that will not cooperate with the external extractive agenda. We can recognize that the rising mental and chronic health crises shine a light on our unconscious personal and collective resistance to participate in systems that are degenerative and opposite of life-affirming. Maybe the first seeming psychic or physical contamination can be seen as an invitation to understand that sterility is a story, ready to disintegrate.

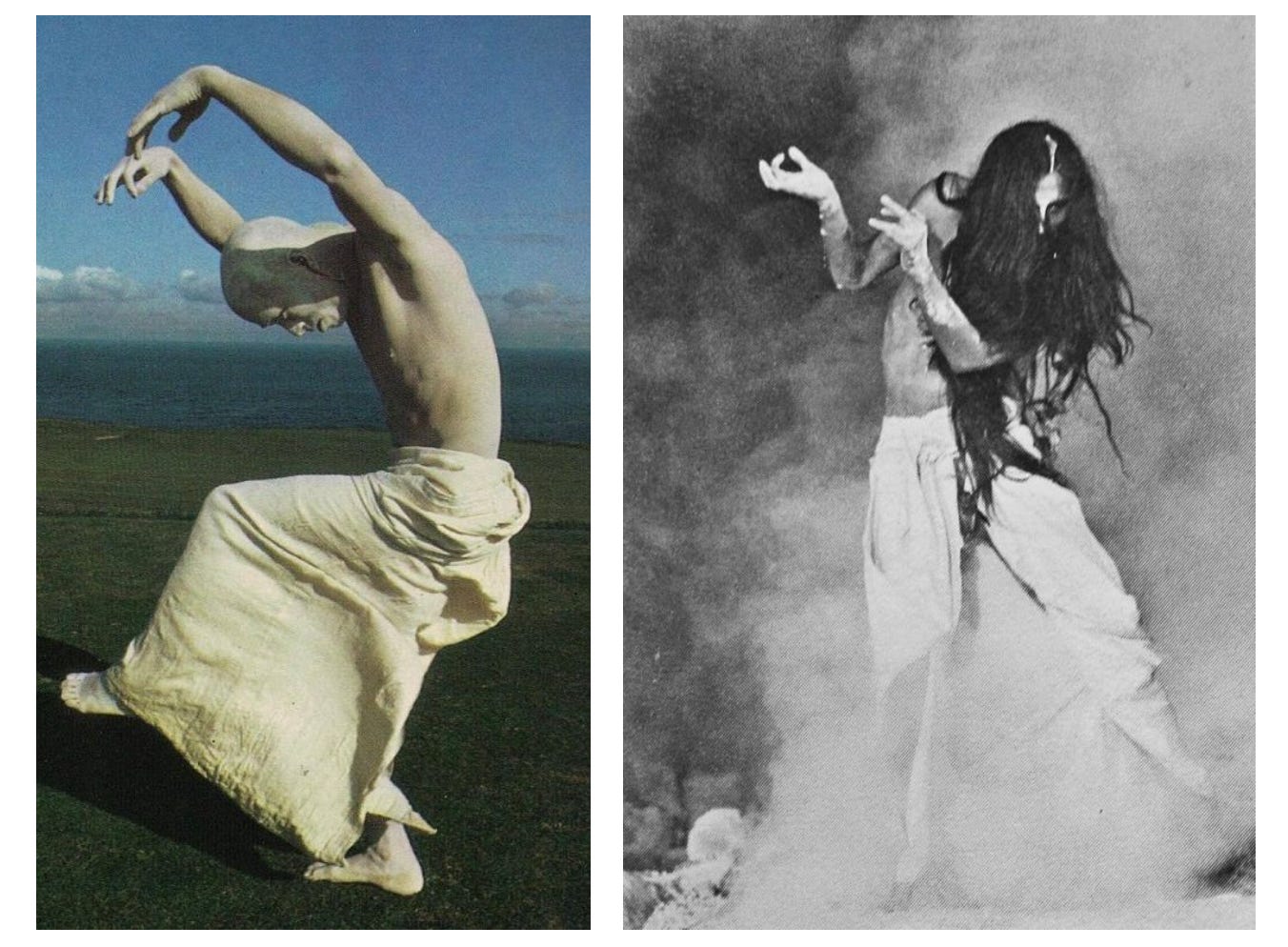

By externalizing mycelium from subterranean worlds into a sculpture, the project makes an analogy of bringing the alienated and contaminated parts of ourselves into the light of consciousness. Out of the subconscious (subterranean) to conscious and visible (above the ground). Alternative movement practices, such as the contemporary Japanese dance Butoh (舞踏, Butō), invite us to perceive the body as an archeological site: “to dig up gestures or figures that have been buried in the darkness of history, and to float them onto the white-painted flesh”.

Mycelium too, with its white fleshy texture, floats up the fugitive, the alienated. The body of mycelium always shapeshifts into the correspondence of another body—roots, underground critters and bacteria, soil, wood, and perishable materials, surrendering themselves into new shapes and decomposition. Mycelium, as an archaeological ontology of memory, is never in one place. It shapeshifts with every change as the memory of the landscape transforms with every emergence, birth, and loss in that landscape. If we are able to converse with this part of the underground landscape, it might bring us closer to memories, truths, and intuitions that can only be held by a long-lasting psychic remembrance. Which, in many times, does not subside in the mind, but in the body and the subterranean awareness.

Fungi have shown their capacity to metabolize contaminants and soil pollutants such as heavy metals. The deliberate introduction of fungi into the soil with the purpose of healing and regeneration is called mycoremediation. To bring life where the equilibrium is lost. The fugitive alien is not the source of illness anymore, but the medicine that the soil needs. The one that seemed to cause the problem is now a source of wisdom. We have accepted the refusal to heal as an invitation to explore our psychic geologies, and to ultimately become an archaeological site. Sometimes, healing will show up as a refusal, disguised as contamination.

I will speak more about mineral contamination, soil, and womb in a later essay about Copper.

Transforming Extractive Relationality

“The end justifies the means. But what if there never is an end? All we have is means.”

―Ursula K. Le Guin

The second topic of the project builds on the first one by examining our extractive relating to fungi. While mycelium and fungi are becoming popular, promising, and innovative design choices, one crucial question remains: Are we using the same extractive attitudes towards fungi, masked under the guise of “the greater good”? The rising green growth economy and innovation in the field of bio-fabrication have opened up opportunities to use biomaterials as a means to an end to a more “sustainable” future.

As we discover new ways to generate biomaterials, we risk overseeing the living organisms as a means to an end—deploying the same extractive methodologies as we have done to other living systems and natural materials.

When sharing that I work with mycelium and fungi, many people ask if they can use it somewhere—if mycelium has usability. This question overlooks the essential nature of fungi on Earth and reveals a myopic outlook on human and more-than-human relationships. With discomfort, in a growth-centric society, we can say “Yes, it can be useful: for another biotech venture, zero-plastic packaging, architectural composites, animal meat for leather replacements, or many other innovative solutions”.

A study reveals that 2009-2018 yielded 47 patents and patent applications claiming fungal biomass or fungal composite materials for new applications in the packaging, textile, leather, and automotive industries.

But, to be able to patent an ancient living organism seems problematic and opens up a debate about the ethics of relating towards more-than-human. A limited understanding of what “useful” is, makes us perceive other species only from an extractive lens. In fact, a recent study speculates that fungi evolved on Earth between 715 and 810 million years ago— highlighting that fungal mycelium has been more than “useful”, rather, indispensable and vital for life’s evolution on Earth, including in the development of root systems in plants.

The inquiry into “usefulness” allows the public to shift relating from extractive thought patterns such as “what can I get from fungi?”, and towards wonder, curiosity, and desire to explore fungal intelligence, networks, systems, relationships, and speculate possible sentience. The artwork invites us into humility and reverence toward fungi: how can we learn from fungi, while developing new kinships and relationships with these incredible species? Can we move beyond the means of sustainability and towards regeneration? Scientists such as Jane Goodall or Merlin Sheldrake tell stories of change while living alongside the subject of study: the more we learn about a subject, a species—the more that wholistic knowledge allows us to be transformed into new ways of relating: from extractive to kinship.

How does the public reimage our relationship with fungi — not just from extractive “green growth” lens, but to reestablish an understanding of deep interdependency and care? Can we not only see fungi and mycelium as an emergent design biomaterial but as species integral to our existence? Can we examine extraction practices before mass-industrializing fungal species for “green growth”?

I will let those questions stir onward.

Whatever is not healing, whatever or whoever is refusing within you, is trying to start a different type of conversation with you. It is not a shutdown, but an invitation. Resistance is a gift that can steer us in the right direction, the right inquiry, and ultimately a personal or collective truth wanting to emerge.

Here is another story that inspired me greatly. It was a short conversation with Bayo Akomolafe that actually grounded this project into a deeper meaning.

Here’s an excerpt from our Q&A, that happened during Flourish! session:

Rūta: I feel that my ability to cope with the modern world is slowly disintegrating. I feel a thinning veil between me and the reality of the world: the multi-crisis we are facing, the daily encounters with human and non-human suffering, dying ecosystems, and disappearing species. It is becoming harder to process the brokenness of systems out of my own system. It’s becoming harder to function as a normal and normative part of society. The burnt-out sensitive nervous system cannot regulate the stimuli, nor the heaviness of this time. This alien part of me cannot be socialized back into society. This part of me refuses to heal. No matter what healing modalities I try.

Bayo: “That sentiment you just expressed is deeply theoretically dense. It is generational. And what sentiment am I trying to highlight here?

“I refuse to heal.”

There's a French visionary that has captured my imagination. He lived as a contemporary of François Tosquelles and Jean Oury—these are visionaries that started the institutional psychotherapy movement, which resisted the asylum and its politics during the Nazi occupation of France. In post-Second World War France, this man, I'm speaking of, Fernand Deligny. You might have heard of him, an educator or maybe an anti-educator because he was against <laughs> coddling children. This was a time when about 45,000 people died in the asylum. And not just due to the war or starvation, but also due speculatively, allegedly to the efforts of the Nazi occupation to kill off and discard people that were deemed inadequate, like the people suffering in the asylum, right? So lots of people died. And this is when that movement started to form. Delini was of the opinion that autistic children were not less of, right?

They were not to be healed. There was something powerful about them. And I say this as a father of an autistic son, right? And this is what draws me into his politics. He's dead. He died in 1996, but he's not as popular. He's quite esoteric, but his movement is really catching on, I believe for those who are introducing themselves to his work. He decided to, to leave the asylum and to start these guerrilla, renegade, fugitive communities in the south of France, in a place called Cévennes. It's very, very rocky and unforgiving, right? <laughs>, rocky terrain.

Bayo: He led this community there. And non-verbal autistic children were part of that community. Mind you, he did not try to heal them, to reform them, to explain them. Instead, his work, along with his accomplices was to accompany them, right? Because he noticed that trying to reform them was to impose the supremacy of what we might today call neurotypicality.

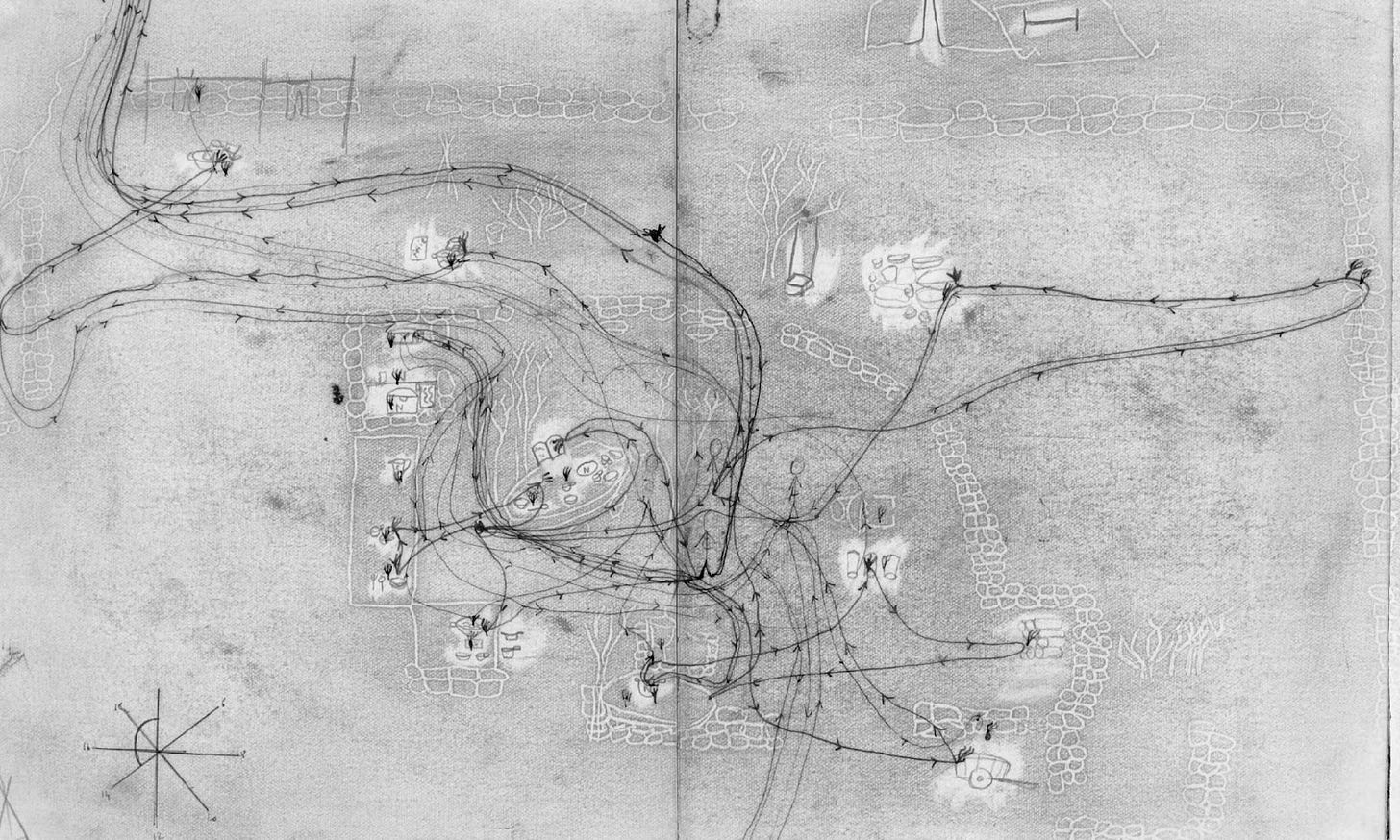

So he was like “I refuse to heal them. I'm gonna accompany them. You know what we're gonna do? We're gonna start cartographical projects. We're gonna trace their wandering”. So he called it lignes d’erre, which is wander lines. And the accomplices would trace the so-called mad wanderings of these children as they just wandered in those large fields. Here's what's very interesting about this. You call them non-utilitarian wander lines, right? But there was something about them that was quite fascinating because they discovered that those children seemed to be tracing out unknowingly the underground circuits of water.

Bayo: Think about that. Their so-called nonsense walking was tracing out the root and the passage of water underground. That's the question I ask: what are we missing with our so-called normalcy? What are we missing with our so-called wholeness? You know, I do not dispute the ways or critique the ways people use wholeness. Semantics always comes in. You can use it in any way you want. I'm using it in a very strict sense of noticing that sometimes when we speak about wellness or health, we are reinforcing colonial boundaries of closure. We're reinforcing the walls with which we have used to name our bodies.

And I like what I've learned here in India. I'm married to an Indian, my children are Indian, my friends are Indian. The land has taught me something. It says in a proverb that “name the color, blind the eye”. Let me say this, sister, I convey blessings on you, and I ask my ancestors to bless you, to bring fugitive communities that will support you and those of you in such circumstances. I'm in that circumstance as well. We don't want to close you up. We don't wanna be closed up.

We want the cracks to breathe because that's how novelty—that's how transformation happens: in that place where we say “no, I don't want to heal. I'm gonna stay with this trouble and see where it takes us.”

And those wander lines do magic things. Yeah. I'll just say that.”

Thank you for reading and delving deeper into the topic with me. I feel deeply grateful to everyone who has been reading the newsletter so far. If you feel called to support me, you can become a paid subscriber of Regenerative Transmissions.

stirring - moving - on point - there is to be no adaptation to cruelty - that the current paradigm isn't sustainable is a derivative of its utter cruelty. transforming through an ongoing oscillation of staying in the cracks, emerging, back into the cracks, emerging

Gosh I love your mind. Such beautiful reflections and stories on a topic close to my heart and often in my mind. I often ask myself ‘character flaw or culture flaw’? For a long time I thought I was broken for not fitting and for my deep bone tiredness, but now I wonder whether this society is functional for all of us...not just the few that can maintain productivity and sustain constant energy.